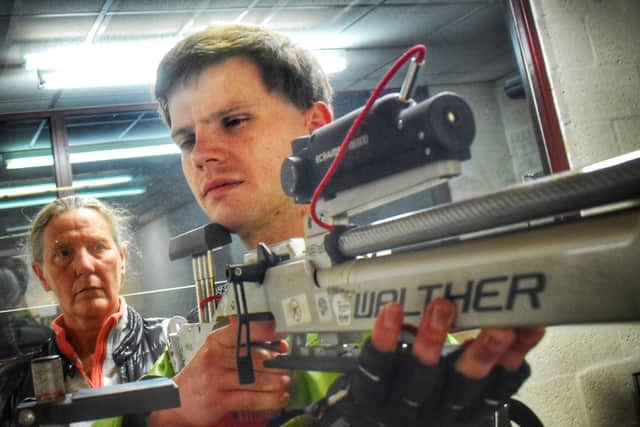

Special Feature: Blind shooter Michael on a mission to turn Paralympic dream into reality

Melton Times reporter Chris Harby meets a reluctant pioneer.

“Normally the first question people ask is ‘how do you do it?’

“We learn a script to explain it.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s safe to say a fair portion of our interview asks nothing new of Michael Whapples.

There are a few questions he could answer on auto-pilot, perhaps accompanied by a heavy sigh if he wasn’t so polite.

“I need someone to help me line up at the beginning, but the shot is all down to me,” he explains, patiently.

“For me, shooting is a very independent sport, and that means a lot.

“When I achieve something, that’s my achievement.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“On the other hand when I have a bad day, I have to admit that was me as well!”

Visually impaired shooters take aim from the same distance as their sighted counterparts - 10 metres - and face the same impossibly small target face.

Four-and-a-half centimetres across, with each ring offering a two-and-a-half millimetre width, shrinking down to just half-a-millimetre for the bull.

The air rifle is also identical, save for the sighting mechanism.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAudio equipment replaces the telescopic sight, a development which Whapples himself was involved in.

Through earphones connected to the audio aid, the shooter hears a pitch which grows shriller and faster the closer the rifle aims towards the centre of the target.

Whapples was born with aniridia, a rare eye condition affecting just two in every 100,000 people, which led to the ensuing glaucoma and the significant damage.

“I’ve always had visual impairment,” he explained.

“I could read very large print when I was young, then it just deteriorated.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It got to where it is now around 2006 when I had an infection which took the sight that was remaining.”

I’m sure many of us, if faced with the looming certainty of complete sight loss, would choose denial.

But Whapples was encouraged to face up to his lot from an early age by parents, both blind, who bred self-reliance and independence in their son.

“It was known I was going to lose my sight when I was young.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“People try to teach you what will happen, but maybe I resisted learning some of it.

“Neither of my parents can see and they would say ‘we managed so you are going to’ - they were very supportive.

“Sometimes the best thing is just to say ‘no, you have to do it’.

“It may be tough at the time, but it made me more confident.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Others whose parents were a lot more protective were less confident.”

Perhaps it is this grounding, enforced by one of life’s toughest scenarios, which has shaped his competitive outlook.

To ignore the limits that sight loss is believed to impose, to find possibilities first, and restrictions last.

Whapples (34) was introduced to shooting at a school for the blind and visually impaired in Worcester.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It had the equipment and the club was on the school campus so I thought I’ll go and see what it was about. It soon hooked me; I’ve not been able to stop.”

Not only did he find his new pursuit addictive, he also found he was pretty good at it.

Using an in-built perfectionist streak to hone this latent talent soon got him noticed.

“Back in about 2000 we always had a team go over to the Dutch Open, and that was the year I first got selected, so I thought ‘I’m doing okay at this’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Back then the rifle was on a support stand at a huge target.

“Over time I started doing it without the support stand, and at smaller targets, and then eventually against sighted shooters.”

He joined Holwell Rifle Club soon after beginning a physics degree at Nottingham where a potential career path into science took a slight diversion into software design.

“When I went to university, getting stuff in braille was difficult, so because I had done computer programming I started writing software to get around the problem.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I thought it was really interesting and that’s how I got into software development.”

Once the degree was complete, shooting guided his next house move to Melton.

We meet at Whapples’ second home, his rifle club, tucked discreetly down a bumpy track behind a row of terraced houses in the small village of Asfordby Hill.

If its surroundings appear modest, its membership is anything but.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe club boasts an impressive alumni - British internationals, Olympic hopefuls, a Commonwealth Games medallist - among whom Whapples has become one of its most decorated shooters.

His unprecedented move to compete against sighted shooters was borne of ambition.

By the time he took the plunge five years ago he was already in a league of his own in domestic VI shooting.

Winning umpteen national and British VI titles, he could have stayed put and kept on cleaning up.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut Whapples was not given an easy life and is not interested in the easy option.

The stakes had to be raised.

He needed tougher challenges to develop his shooting, and further his ultimate aim of competing on the Paralympic stage.

“It was a bit of wanting another challenge, and also we knew where the international thing was going with the smaller targets.

“As we moved towards getting ready for the Paralympics, people were saying it’s got to be harder and use the same smaller target a sighted person uses.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“In the longer term I would love to see myself at the Paralympics at some point. That’s my ultimate goal.”

He hesitates: “No, that would be to win it!”

Last year, Whapples became the first visually impaired marksman to compete in a national competition for sighted shooters, and this spring entered the British Airgun Championships.

“It was a way of saying, right you’re going to shoot on smaller targets and under competitive pressure so you might as well get used to it.”

The strategy has helped his career scale new peaks over the last 18 months.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGold at the prestigious Hannover International last year, a World Cup silver, and then two months ago the pinnacle of his career so far, a bronze medal at the World Shooting Para-Sport Championships in Australia.

His upturn in international fortunes also coincided with the recruitment of a new coach.

Since joining forces with Pauline Thornton, an international shooter and Holwell clubmate, around two years ago, she changed everything from posture to how how he shoots and also added the prone discipline to Whapples’ armoury.

As well as honing technique in training, she is also his assistant at competitions.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHaving competed at the top, Thornton has high standards and is honest in her appraisal.

She is also not there to make life easy in training.

On the range the radio is on.

It’s not blaring, but it’s certainly not the pin-drop silence you’d expect in a sport where concentration is key, let alone for a blind shooter completely reliant on sound.

But the background chatter of Jeremy Vine and his excitable callers hasn’t been left on by mistake.

“When we train we make the range as noisy as possible because when you go to international competition it’s not quiet,” she explained.

“So sometimes we try and put him off.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhapples added: “When we get down to the medal places they encourage the audience to start clapping to really stack on the pressure.

“As a shooter all you can do is try and block it out.”

Another obstacle employed in training is the wobble board which he must stand on while shooting to improve balance.

“I do yoga to improve my balance and flexibility. It also helps you to focus on yourself.

“Sometimes shooting’s better when you don’t think and just do it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“People say 20 per cent is technique and 80 per cent is mental, something along those lines.”

Perfecting this mindset and technique in training is one thing, doing it under the pressure of competition quite another.

The competitive arena is impossible to replicate in training, no matter how loud you turn up the radio.

Standing finals open with two sets of five shots, each of which must be completed in 250-second blocks, and then the stakes are raised.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Then everyone gets 50 seconds to take one shot, then it’s another single shot on command, then the last-placed person drops out, then another two shots on command, and the last-placed person drops out, and it’s like that from 24 down to one.”

Each one of the mentally-sapping shots is crucial. One slip, one bad shot will most likely cost the whole shooting match.

“It’s quite draining. Immediately after a competition it takes a few minutes for me to come out of my zone.

“People come up and say well done, but I have to ask them to let me sort myself out first.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNerves are the shooter’s biggest enemy, they cost Whapples a world championship medal in his opening discipline in Sydney.

While technique can be mastered through endless repetition and minute tweaking, taming the mind and its subconscious thoughts is much more complex.

The responsibility of being an unofficial trailblazer for his sport is another weighty distraction.

“I get more nervous against sighted shooters because I feel I’m representing visually impaired shooters.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Against sighted people I feel I have a point to prove - I want to show that we can shoot well.

“I don’t want to go in and not perform as well as I normally do and have people say ‘well done’ and feel a bit patronised.

“I want to feel I’ve achieved something when people say well done.”

When Whapples comes to look back on his career, his lasting legacy could be for an achievement at the committee table rather than with rifle in hand.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIf he does one day find himself embroiled in Paralympic competition, his rivals would have good reason to shake his hand, regardless of whether he lands his dream gold medal or not.

For the last eight years, he has been a driving force to get visually impaired shooting accepted into the Paralympic pantheon.

“I got into it by accident,” he explained.

“Back in 2011, the person in charge of the International Blind Sports Federation (IBSA) was wanting some help.

“I said I was prepared to help, but I needed to be nominated to get on the committee so the Swiss delegate agreed to do that.

“Then I found out they were nominating me as chairman.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDelving into the world of governance, it soon became clear rivalries were not confined to the range. Diplomacy was key.

“In the past there has been a lot of friction between the two (IBSA and World Shooting Para Sport) and I thought it’s time for us to co-operate more so I went down that line.

“I also knew IBSA couldn’t do it on their own. It’s been tough trying to co-operate and hand over the power, but I think it was the right thing for the sport.”

Sight classification was another key part of Whapples’ work, to ensure the sport was robust enough to stand up to scrutiny.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“They said if you want to be in the Paralympics you have to come up with sport-specific sight classes to make sure people are competing on a level playing field.

“We had to develop an entirely new system.”

But after years of research, there appears to be light at the end of the tunnel.

With the classification of Paralympic sports a hot topic for broader debate, there is still more evidence to find and bridges to cross.

But Whapples is confident enough to name target dates.

“I think there is a realistic chance now. 2020 is definitely not going to happen, but in 2024, could it be a demonstration sport?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There is an outside chance, but I think we’re eventually looking at 2028.

“I’m just keeping my fingers crossed, as shooters can be some of the oldest competitors in the Paralympics!”

This later estimate would mean keeping skills at their peak for the next decade - he will be 43 by the time the Paralympics hit Los Angeles.

But the need to train is not the only reason he plans to spend less time in meetings.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMaybe to achieve this ultimate goal, to again push beyond the limits that life has sought to impose, it’s time to become a little more selfish.

“I see my future more as an active competitor, continuing my work in promoting the sport and showing what is possible.

“While I was involved in governance there was a lot of potential for conflict of interest if I competed, so I’m moving to less of a governance role.

“Wanting to move the sport on was why I got involved in governance.

“But then do I want to move a sport forward that I can’t compete in?”